Part 3: Applying the CBT Model of Emotions

Unlike more complex or traditional forms of talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy simplifies the process of understanding and changing emotional processes. According to CBT, there are just a few powerful components of emotion to understand and work with. The benefit of this simpler approach is that it clarifies problems and the solutions needed to solve them such that with a little practice, anyone can understand how to do it.

The Three-Component Model of Emotions

From the CBT perspective, there are three components that make up our emotional experience. They are thoughts, feelings, and behaviors:

Thoughts

Thoughts refer to the ways that we make sense of situations. Thoughts can take a number of forms, including verbal forms such as words, sentences, and explicit ideas, as well as non-verbal forms such as mental images. Thoughts are the running commentary we hear in our minds throughout our lives.

Feelings

The term feelings here doesn’t refer to emotion, but the physiological changes that occur as a result of emotion. For instance, when we feel the emotion of anger, we have the feeling of our face flushing. When we feel the emotion of anxiety, we have the feelings of our heart pounding and muscles tensing. Feelings are the hard-wired physical manifestation of emotion.

Behaviors

Behaviors are simply the things we do. Importantly, behaviors are also the things we don’t do. For instance, we might bow out of a speaking engagement if we feel overwhelming anxiety. On the other hand, if instead we feel confident, we might actually seek out those sorts of engagements.

Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

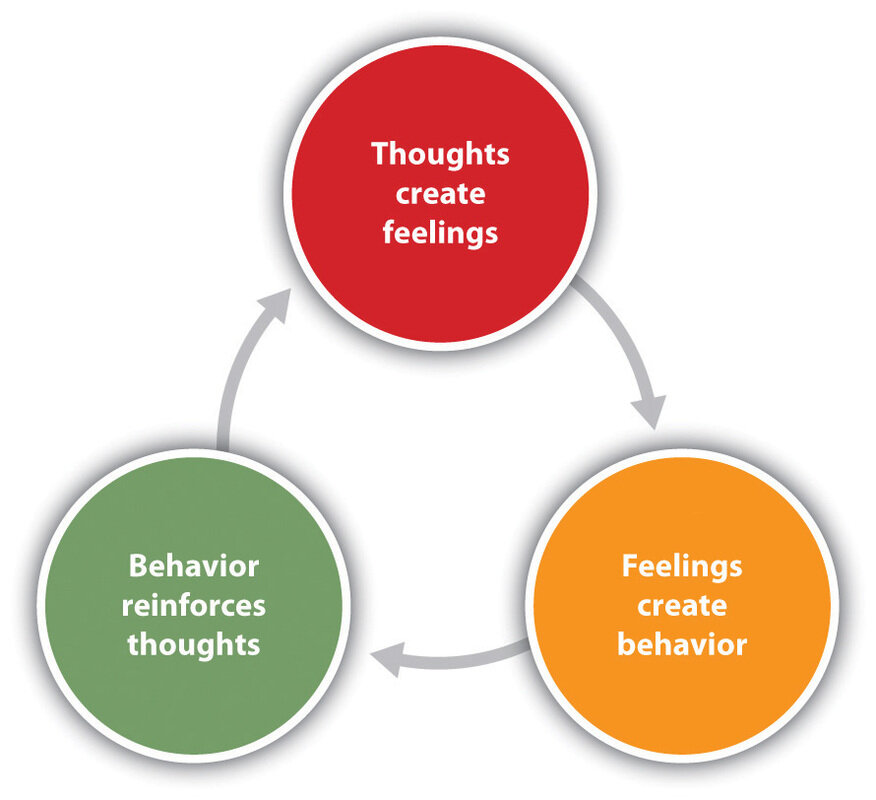

In a nutshell, a situation unfolds, and our thoughts about it generate feelings, leading to behaviors that influence the situation positively or negatively. This cyclical process repeats, emphasizing the interconnectedness of thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and their impact on ongoing situations.

The cognitive triangle visually represents the interconnectedness of thoughts, emotions, and behavior. It illustrates how thoughts influence emotions, leading to actions that, in turn, affect thoughts, creating a continuous cycle. This cycle persists without intervention to disrupt the pattern.

As discussed in the introduction, each component interacts with the other to create moods and emotional patterns. Changing one component results in a chain reaction that changes the others.

How Thoughts Impact Feelings and Behaviors

Terry has suffered from depression on and off throughout her life. She has noticed the depression begins to set in after some kind of a major setback in her career or social life, but has thus far been totally unable to reverse course when she begins to feel her mood worsen. She is currently experiencing significant depression that started after she was laid off from her job due to an economic downturn.

Terry signed up for a networking event in her field, hoping to learn about potential job prospects. The day of the event, as she was contemplating getting ready to go out, she had the thoughts “This mixer probably won’t result in anything. All the good jobs are already taken, and when people find out I’m out of work, no one will consider me for an interview. It’s a huge amount of energy for a lousy payoff.” After considering these points, she felt heaviness and fatigue wash over her. She decided to lie down for a bit, but she only felt less energy after having laid down in bed for twenty minutes, so she decided not to attend the event. That night before bed, she had the thought, “I really wasted the day. I’m never going to get a job, and I’m never going to feel better.”

In this example, it’s pretty clear that Terry’s thinking is leading to a negative chain reaction in her feelings and behavior. Having thoughts that she won’t succeed only results in her having stronger feelings of depression: heaviness and fatigue. These thoughts also provide a reason for her to engage in a certain behavior: avoiding the event. Finally, it’s clear how the feelings and behavior end up reinforcing her negative thoughts, thus continuing this negative feedback loop.

How Behaviors Impact Thoughts and Feelings

Albie has had panic attacks most of his life. When he has a panic attack, he has feelings of tightness in his chest, his heart pounds, and he gets lightheaded. Since beginning a demanding graduate program in engineering, his panic attacks have been on the rise. He has learned to engage in the behavior of quickly returning home or hiding in the bathroom whenever the feelings of anxiety begin, but recently, this has resulted in him missing a significant portion of class, and he has fallen behind. Whenever he thinks about how behind he is, he feels an upsurge in panic symptoms, and the cycle ensues. Also, he has recently begun to worry that he will “lose control” and “go crazy” if he is unable to escape to someplace private when he experiences panic.

Here, it is Albie’s reactions to his feelings that are the major source of the problem. While panic attacks are definitely unpleasant, they won’t cause him to “go crazy” or “lose control,” but having these frightening thoughts certainly causes his anxiety and panic to rise. Because the main coping skill he has for his anxiety is escape and avoidance, his behaviors are only serving to bolster the thought that panic attacks are dangerous.

Paradoxically, this only causes more panic attacks. If he were to reverse the pattern of avoidance and actually ride out a panic attack in class, he might find that they are short-lived (usually lasting only a few seconds to a few minutes) and certainly do not cause him to go crazy or lose control. Moreover, it’s unlikely anyone else would notice it was even happening. However, because his behavioral routine does not allow for this evidence to see the light of day, he feels trapped in a cycle of panic and avoidance.

How Feelings Impact Thoughts and Behaviors

Joni recently found out a close friend was diagnosed with a debilitating disease. Understandably, Joni had feelings of sadness, a pit in her stomach, and fatigue when she heard the news. As she went through her day, she had more negative thoughts about her job than usual, such as “I’m wasting my life here” and “No one takes me seriously.” Feeling hopeless about her career, she engaged in the behaviors of not participating in the day’s meetings and giving up after some difficulty completing a report. After work, when having dinner with her partner, Joni had uncharacteristically bleak thoughts that “This relationship is not going to last” and that she would “be alone for the rest of her life.” Joni was silent for much of the meal and felt awkward and lonely.

Sadness is a natural feeling to have when you get bad news about a loved one. In this example, the sadness Joni felt about her friend seemed to bleed into her feelings about work and her romantic relationship, which were not at all related to her friend’s news. This is because her feelings of sadness essentially tinted her view on everything, not just her friend. Because she had strong feelings of sorrow, her thoughts, no matter where she turned them, were affected by that sorrow. Consequently, she withdrew from important activities at work and from connecting to her romantic partner. By disengaging from important parts of her life, she set the stage to feel even worse, ensuring that the cycle of negative emotion continued.

By recognizing the cascading feedback loop of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors influencing and escalating each other, you develop a powerful insight into harmful cycles of emotion. The goal of cognitive-behavioral therapy is to map out these networks in order to undo them. Just a few, consistent interruptions of these cycles of emotion can undo them altogether. The depression pattern is undone by adopting less negative ways of thinking and engaging in rewarding activities rather than avoiding them.

Developing Insight with the CBT Model of Emotions

If you want to learn to manage your mood and act more effectively in the face of challenging situations, it is crucial to develop the ability to identify and distinguish between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Usually, when we are overwhelmed, emotion feels like a tidal wave of discomfort, but we don’t stop to clarify the components of that emotion. As a result, we have great difficulty doing anything about our mood other than waiting for it to pass all on its own.

By breaking an emotion down into its parts in the moment, we develop crucial insight into the factors that are maintaining or worsening our unpleasant emotions. Piecing out the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, we discover how to intervene: which thoughts need to be redirected, what behaviors are making the problem worse, etc. Practicing the skill of identifying all of the parts of the emotion using the CBT model, we become more skillful at steering our moods toward more effective responses, thinking and acting skillfully in the moment to actively handle the challenges of the situation at hand.

Identifying Components of the CBT Model:

During the upcoming week, choose several situations in which you feel strong, uncomfortable emotions and apply the CBT model to identify each of the components of that emotion. If you have difficulty identifying some components, that’s okay. Just note the parts that seemed the most difficult to clarify, and pay special attention to them as the week goes on as you continue to track thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. For example, if you’re stuck when it comes to identifying thoughts, make sure you apply more effort to noticing your thoughts periodically throughout the week. Just like strengthening a muscle through repeated exercise, practicing identifying the parts of emotion will become easier over time.

Before moving on to the next part of the program, spend some time completing this worksheet by identifying difficult situations and tracking the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors arising. In the beginning, it’s best to do this after the situation has passed and some of the dust has settled. With practice, you’ll find that it becomes easier, such that you can pause in the middle of a situation to become grounded in the CBT model.

CBT For Anxiety Disorders: A Practitioner Book. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, New Jersey. – Simoris, G., Hofmann, S.G. (2013).

Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Second Edition: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press: New York. – Beck, J.S. (2011).

Treatment Plans and Interventions for Depression and Anxiety Disorders, Second Edition. The Guilford Press: New York. – Leahy, R.L., Holland, S.J.F., McGinn, L.K. (2011).